Although French commercial law is tending towards uniform application throughout France, it takes on many different forms in the overseas collectivities. Far from being a simple variation of French law, commercial law in the overseas collectivities is the product of a history, a development policy and specific constitutional statutes that shape an original legal landscape. This article provides an overview of this branch of law, focusing on its particular judicial organisation, in particular the mixed commercial courts, and giving an overview of the main legislative adaptations. The specific features of each territory, which merit in-depth analysis, are dealt with in greater detail in our dedicated articles.

Understanding the context and principles of overseas commercial law

The uniqueness of business law in overseas France is no accident. It is rooted in the Constitution itself and is designed to meet specific economic objectives, seeking to promote sustainable development that reconciles the unity of the Republic with local realities.

The constitutional framework: Article 73 and Article 74, the basis for specific features

The fundamental distinction in overseas law is based on two articles of the Constitution. Article 73 enshrines the principle of legislative identity for the overseas departments and regions (Guadeloupe, French Guiana, Martinique, Réunion and Mayotte). In theory, national law (and in particular the Civil Code and the Commercial Code) applies automatically. However, this same article authorises adaptations to take account of the particular characteristics and constraints of these territories. Conversely, Article 74 establishes a system of legislative speciality for the overseas collectivities (French Polynesia, Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon, Wallis and Futuna, Saint-Barthélemy, Saint-Martin) and New Caledonia (governed by specific provisions). In these territories, laws and regulations only apply where expressly stated. This constitutional duality is the keystone of all the differences observed in business law.

The search for economic efficiency and the simplification of overseas legislation

Beyond the institutional framework, commercial law in the French overseas territories is influenced by a desire for simplification and economic efficiency. Aware of the structural challenges of these territories (remoteness, small market, approach costs and the fight against high living costs), the legislator has often sought to adapt the rules to stimulate local initiative, investment and entrepreneurial dynamism in each sector of activity. This pragmatic approach is reflected in adjustments in various areas, from collective procedures to competition rules, with the ambition of providing a legal framework that supports economic growth rather than constraining it.

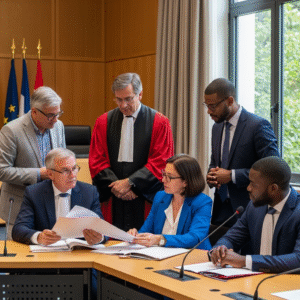

The commercial judicial system in overseas France: a unique model of mixed justice

It is undoubtedly when it comes to the organisation of the judiciary that the overseas territories have the most distinctive features. Rather than transposing the French consular model, most overseas territories have opted for an original solution: the mixed commercial court. For an in-depth understanding of the mechanisms and stages involved in taking legal action, consult our complete guide to commercial court proceedings.

Mixed commercial tribunals (MCTs): foundations and history

The idea of a mixed judiciary, combining professional magistrates and judges from the business world, is not new. It was introduced on 26 April 1928 in the oldest departmentalised colonies (Guadeloupe, Martinique and Réunion) to combine technical knowledge of the law with local customs. This model has proved its worth and has gradually been extended, becoming the rule of principle for the local authorities governed by Article 73 of the Constitution, as well as for territories such as New Caledonia and French Polynesia.

Composition of the tmc: chairman, elected judges and registry

The mixed commercial court is presided over by a career magistrate, generally the president of the judicial court or one of its vice-presidents. This guarantees compliance with the status of magistrate and procedural rules. Alongside him sit elected judges, tradesmen or craftsmen chosen by their peers. Their number, higher than that of the professional judges on the bench, ensures strong representation of the business world. The conditions of eligibility and election procedures for these judges are modelled on those for consular judges in mainland France, with a few adaptations. The court registry, traditionally a public service, has been reformed with the aim of entrusting it, as in mainland France, to public and ministerial officers.

The specific nature of the mixed judiciary in Wallis and Futuna

The territory of Wallis and Futuna has an even more original form of mixed justice. In the absence of a dedicated court, it is the court of first instance that deals with these disputes. When it rules as a panel, it calls on the services of lay assessors. These lay assessors, who do not necessarily come from the business world, take part in the judgement alongside the judge, illustrating the way in which the judicial system has been extensively adapted to the realities of an area with a low volume of litigation.

Jurisdiction of mixed commercial courts: substantive and territorial

The jurisdiction of the TMCs is largely aligned with that of their counterparts in mainland France. They hear disputes relating to commitments and contracts between traders, the obligation to comply with the articles of association of commercial companies and commercial acts. However, there are special features, particularly in relation to collective proceedings and competition.

Substantive jurisdiction: alignment with ordinary law and special features in insolvency proceedings

In terms of business difficulties, the TMCs have jurisdiction to initiate and monitor safeguard, receivership and liquidation proceedings. One notable difference with mainland France is that there are no specialised commercial courts to handle cases involving the largest companies. The TMCs therefore retain jurisdiction regardless of the debtor's turnover or number of employees, a solution justified by the local economic fabric. If your overseas company is facing difficulties, our essential guide to the observation period in insolvency proceedings offers valuable insights into this critical phase.

Territorial jurisdiction and validity of jurisdiction clauses

The rules governing the territorial jurisdiction of the MCTs are largely based on the ordinary private law of civil procedure. In principle, the court with jurisdiction is that of the defendant's domicile or registered office. The validity of jurisdiction clauses, which allow merchants to choose a court in the event of a dispute, is also recognised. However, there are exceptions, such as in French Polynesia, where the local code of procedure invalidates any clause conferring jurisdiction on a court outside the territory, thereby protecting local jurisdiction.

Competition litigation: centralised jurisdiction and territorial inapplicability

The treatment of anti-competitive practices is an area where the specific nature of the overseas territories is strong. It has a direct impact on the distribution sector, wholesalers and, ultimately, consumer prices. For reasons of efficiency and expertise, jurisdiction is often centralised. For example, the TMC in Fort-de-France has jurisdiction over Martinique, Guadeloupe and French Guiana. For Réunion and Mayotte, jurisdiction is even transferred to the Commercial Court in Paris. What's more, in New Caledonia and French Polynesia, by virtue of their extensive internal autonomy, national competition law is simply inapplicable, replaced by local regulations implemented by a local authority. Anti-competitive practices are strictly regulated; learn to identifying abuses of a dominant position and how to protect yourself against them.

Second-degree commercial courts and appeal procedures in overseas France

The organisation of appeals against CMT decisions is closer to ordinary law. The originality observed at first instance is tending to disappear at appeal level, with one notable exception.

Jurisdiction and organisation of appeal courts in French overseas departments and territories

Appeals against judgements handed down by the TMC are possible when the interest in the dispute exceeds a certain amount, known as the "taux de ressort". This threshold is generally aligned with that in mainland France, which is set at €5,000. Appeals are lodged with the relevant court of appeal (Basse-Terre, Fort-de-France, Cayenne, etc.), which rules in a panel made up exclusively of professional judges. For Mayotte, appeals are handled by a division of the Court of Appeal in Saint-Denis de La Réunion, sitting in Mamoudzou.

The special nature of the appeal court in Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon

Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon has a unique organisation at second instance. The High Court of Appeal, which hears appeals against commercial decisions, is not made up entirely of career magistrates. As is the case in Wallis and Futuna at first instance, the judging panel includes lay assessors. This is the only example of a mixed commercial judiciary at appeal level in the national judicial system.

Legislative and regulatory changes to commercial law in overseas France: a comparative table

Each overseas territory has its own set of commercial rules, with varying degrees of derogation from ordinary law. For an overview of the rules governing fair trading, our complete guide to the non-competition obligation in commercial law is an essential resource for securing any contract.

Mayotte: between assimilation and legal particularities

Now a département, Mayotte is subject to the principle of legislative identity, but retains a number of specific features. Business law has been adapted to cover commercial leases, payment deadlines for certain goods and collective proceedings. The aim of these rules is to support the island's transition to ordinary law, as set out in the Order of 26 April 2012, while taking account of its economic and social context. Discover the specific regimes and essential adaptations of commercial law in Mayotte to understand local issues.

Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon: a reduced but persistent legislative speciality

Although governed by Article 74, Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon largely applies ordinary law. The derogations are targeted and concern, for example, the inapplicability of certain provisions on leasing or commercial leases. Other rules are simply adapted to take account of specific local tax and administrative features.

New Caledonia and French Polynesia: autonomy and application of ordinary law

These two local authorities enjoy a high degree of autonomy. While many of the provisions of the national Commercial Code are declared applicable there, they coexist with a large body of local regulations ("lois du pays"), which are similar in scope to an organic law. There are some notable exclusions, particularly in the area of competition law, where metropolitan law is completely excluded. To find out more about the specific features of this territory, see our article on the commercial law in French Polynesia details its unique system and the role of the Papeete court.

Wallis and Futuna and Saint-Barthélemy/Saint-Martin: special features and maintenance of ordinary law

For these territories, the principle is the application of ordinary law, unless otherwise stated. Wallis and Futuna has a number of special features linked to its customary status, with notable exclusions in the areas of commercial leases and insolvency proceedings. Saint-Barthélemy and Saint-Martin, former communes of Guadeloupe, retain a broad application of ordinary law, the adaptations being mainly of an administrative and fiscal nature.

The role of judicial representatives and the public prosecutor's office in insolvency proceedings in the French overseas departments and territories

Dealing with business difficulties in overseas France involves a number of players whose role is sometimes strengthened by specific local circumstances, in particular the public prosecutor and court-appointed agents.

The public prosecutor: a key player with growing prerogatives

The public prosecutor plays a central role in the conduct of insolvency proceedings. It is informed at every key stage and its opinion is often sought by the court before any major decision is taken (opening of proceedings, adoption of a recovery plan, sanctions against directors). It also has its own powers of action, being able to request the opening of proceedings or the conversion of a safeguard into a receivership. The purpose of this intervention is to ensure the protection of economic public policy.

Legal representatives: administrators, liquidators and their specific missions

Administrators and court-appointed representatives are essential auxiliaries to the law, appointed by the court to assist the debtor (administrator in reorganisation) or to represent creditors and realise assets (court-appointed representative and then liquidator). Their tasks are broadly the same as those carried out in mainland France. However, the profession is adapting to new developments, with, for example, the possibility for commissaires de justice (a new profession merging bailiffs and auctioneers) to carry out some of these functions, subject to appropriate training.

Employee representatives and inspectors: functions and specific features in the French overseas territories

In all insolvency proceedings, employees appoint a representative to assert their rights, particularly as regards payment of their wage claims. For their part, creditors may request the appointment of monitors to assist the judicial representative and monitor the progress of the proceedings. While these functions are identical in France, their implementation may be adapted in certain territories, such as Wallis and Futuna, where certain provisions relating to wage guarantees are not applicable.

The complexity of commercial law in the French overseas territories and the diversity of applicable regimes require a detailed analysis and in-depth knowledge of the specific features of each territory. If you have any questions about overseas business law, please do not hesitate to contact us at contact our expert lawyers for personalised support.

Frequently asked questions

What is a mixed commercial court?

This is a special court for the overseas territories, responsible for adjudicating commercial disputes. Its distinctive feature is that it is made up of both a professional magistrate, who presides over it, and lay judges elected by local traders and craftsmen.

Why is commercial law different in overseas France?

This difference stems directly from the French Constitution, which distinguishes between territories subject to legislative identity (ordinary law applies with possible adaptations) and those subject to legislative speciality (laws only apply if expressly mentioned), in order to take account of their specific constraints and characteristics and to promote their development.

Are the rules the same for all overseas collectivities?

No, each territory has its own specific status. The rules vary considerably between an overseas department such as Réunion (Article 73 of the Constitution) and an overseas collectivity with broad autonomy such as French Polynesia (Article 74).

Who are the judges in a mixed commercial court?

There are two types of judge: a career magistrate (professional judge) who chairs the court, and consular judges, who are shopkeepers, craftsmen or company directors elected by their peers to contribute their knowledge of the business world.

Do these courts deal with all commercial disputes?

In principle, yes, but there are some notable exceptions. For example, litigation relating to anti-competitive practices is often centralised in a few specialised courts, sometimes even in Paris, in order to guarantee specialised expertise and support an effective public regulatory policy.

How can their decisions be appealed?

Appeals are generally brought before the Court of Appeal with jurisdiction in the territory, where they are heard by professional judges, as in mainland France. The only exception is Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon, where the High Court of Appeal retains a mixed composition with lay assessors.